One of the tenets of fly casting is that a longer cast requires a longer stroke. With more line outside of the rod, there’s more mass that the rod must move. More mass outside the rod will bend the rod more under full tension.

Whenever a rod bends more, the stroke needs to be longer. To illustrate, consider the end of a back cast and a beginning of a front stroke. A good length of fly line has straightened out behind the caster. If a soft rod is accelerated forward too quickly the rod tip will buckle trying to move the entire mass of the line at once. Since the rod tip readily yields to the mass of the line, the rod tip’s path dips downwards, creating a tailing loop.

To prevent a concave path of the rod tip, it is necessary to accelerate the rod more slowly over a larger arc to bend the rod gradually as the line stretches and becomes more taut. Once the mass of the line has fully bent the rod, then the rod can be accelerated in earnest to get the line speed high enough (and hence its inertia large enough) to cause the line to straighten out in front of the caster when the rod is stopped.

If we understand that stroke length must be proportional with the length of fly line being cast, then all strokes can’t start and stop from 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock. For the sake of this post, however, let’s envision a person casting to our left with a rod arc starting and stopping from 10 to 2. See Figure 1.

During the back cast, after the rod goes past 12 o’clock, the rod tip starts to travel downwards (towards 2 o’clock). And when we accelerate the rod downwards, we drive the line, or part of the rod leg of the line, into the water behind us. See Figure 2.

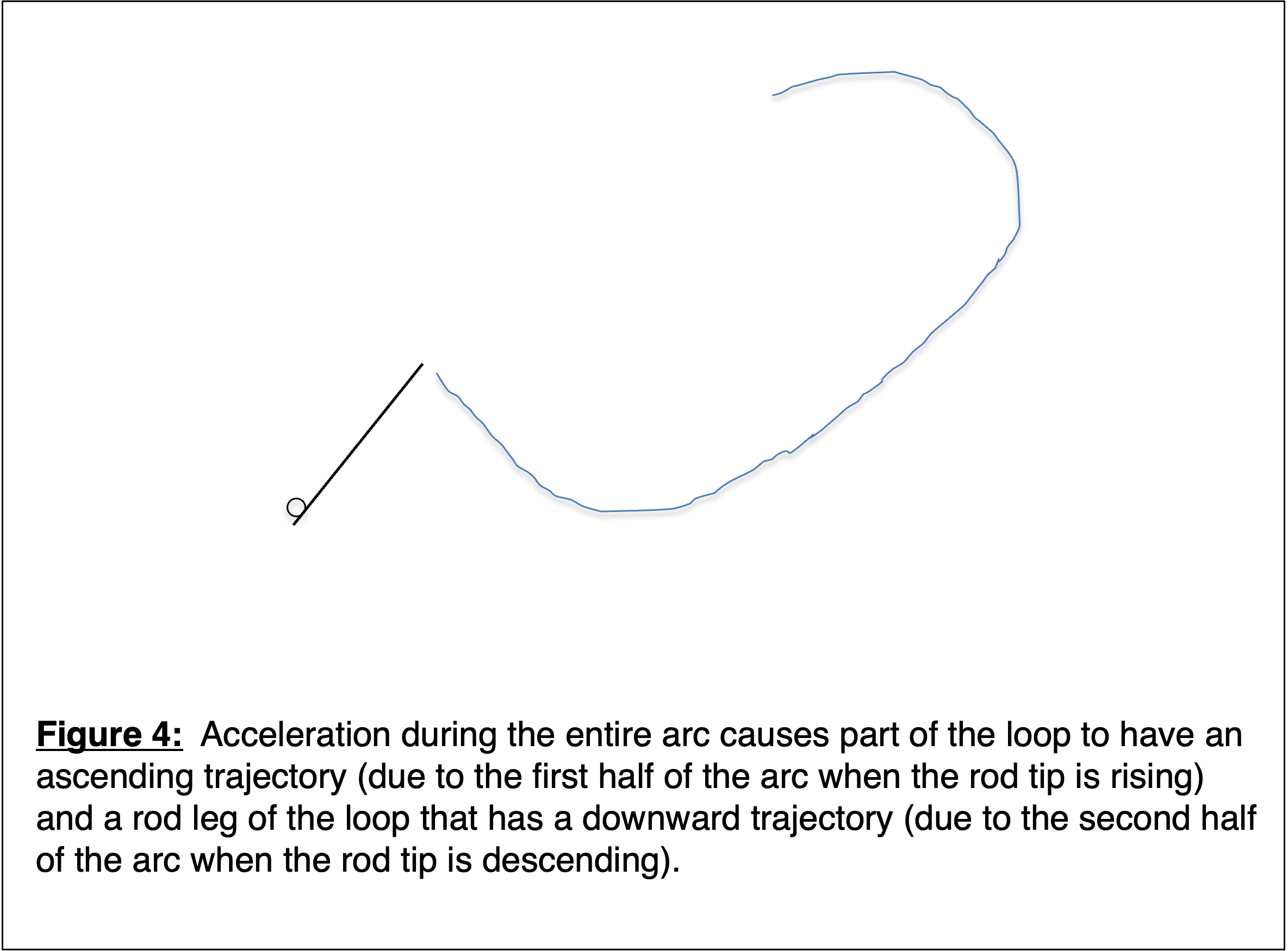

The shape of the loop tells the story. When the rod is accelerated late in the arc, the entire loop will have a downward trajectory. See Figure 3. When the rod is accelerated throughout the arc, however, part of the loop will have an upward trajectory (when the rod tip was rising from 10 to 12), and the part of the loop will have a downward trajectory (when the rod tip was descending from 12 to 2. See Figure 4.

The problem with our back cast slapping the water behind us can be exacerbated by adjustments in our front cast. When our front cast starts to slap the water in front of us (for the same reason that the line hits the water behind us), we stop the rod higher in the front, for example at 10:30 instead of 10 o’clock. To maintain the same stroke length so that we don’t form a tailing loop, it forces the back stroke to stop at 2:30.

A back stroke from 10:30 to 2:30 means that the rod tip is travelling upwards for less than half of the stroke, making an upward trajectory for a back cast – which is what we want – difficult. And when the rod tip is travelling downward for more than half of the stroke, it makes it even more likely that the fly line will slap the water behind us.